As June draws to a close, my son will be finishing up his first year of middle school. It’s a cliché to say “they grow up so fast,” but people say it all the time, of course, because it’s so true. His first day of kindergarten, when he was just four years old, is still fresh in my mind.

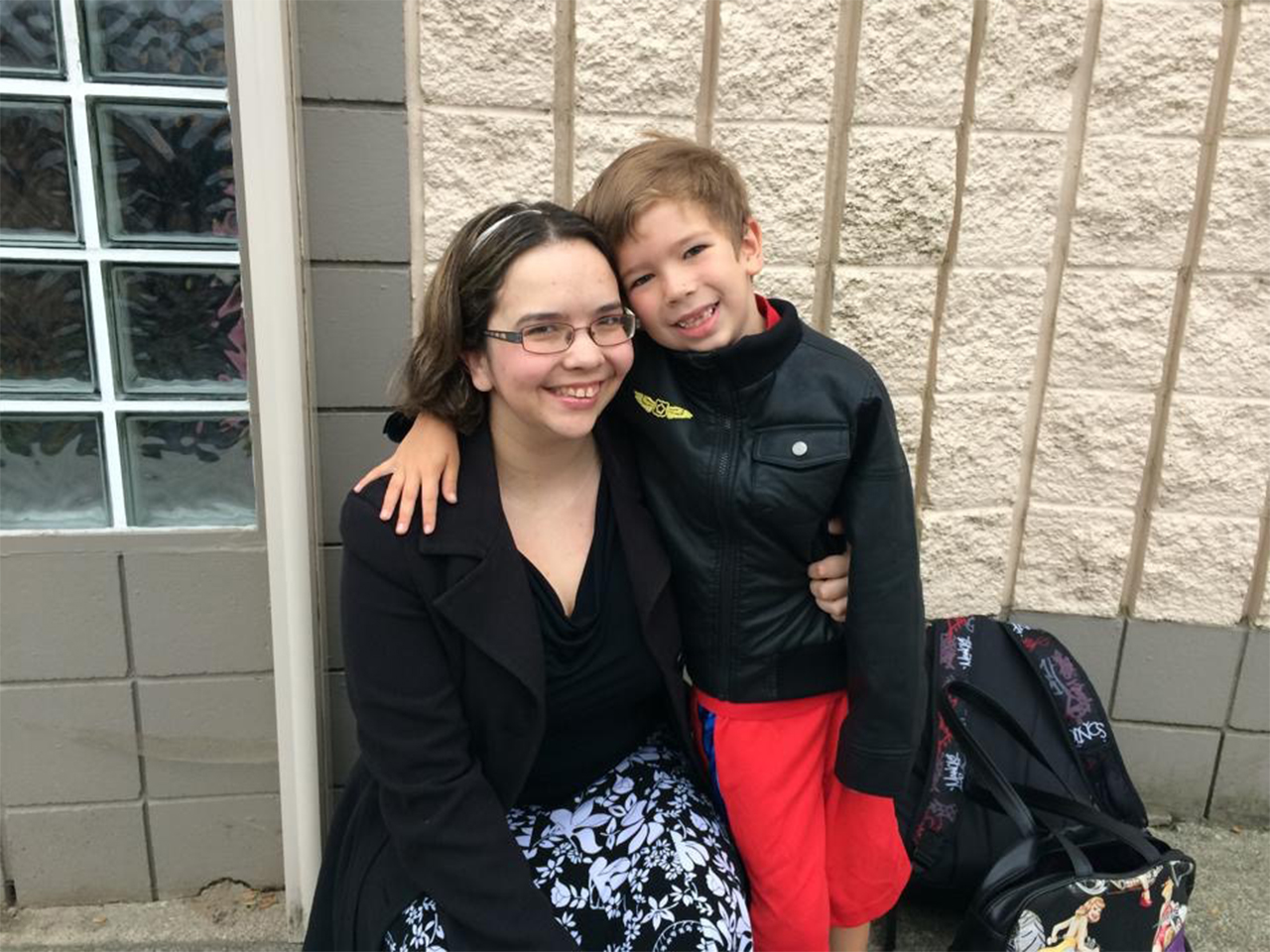

Like many parents, I had a mix of emotions about such a big milestone, but mostly, I felt incredibly lucky that day. I watched as my little boy sauntered off to his classroom, backpack laden with supplies, excited for what lay ahead. On the playground, before the bell rang, he’d posed for pictures and his dad and I did a video interview with him about his aspirations, starting a special family tradition that we’ve continued every year since.

I knew in that moment, watching him walk through the doorway of his kindergarten class, that I was fortunate to be able to actually enjoy my child’s first day of school. I knew he would be in good hands, that we would be back for him in just a few short hours, and that we would listen to him prattle on about all that he had experienced on his first day. I was excited for my little person and all he would learn.

And as an Indigenous mom, I’m keenly aware of what a privilege that is. I knew he would be safe.

This wasn’t the reality of Indigenous moms before me, in the time of residential schools. Many of those moms—not that many years ago—had their kids ripped from their arms by government agents or RCMP officers. They didn’t know when their children would be returned to them. They didn’t know if their children would be returned to them. The reality is that many kids died and never came home.

They didn’t know if their kids would be fed properly. They didn’t know if they would experience physical or sexual abuse. They didn’t know if they would be experimented on. They didn’t know if they would be asked to dig the grave of another student. What happened in those schools was horrifying.

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996—which really isn’t that long ago at all. For over 100 years, more than 150,000 Indigenous children had been legally required to attend residential schools, run by churches and the Canadian government, since the 1880s.

In those days, Indigenous moms sent their kids off to school knowing the “education” that awaited was designed to teach that what was offered in their own homes, in their own communities, in their own traditions, was undesirable and substandard. Their children would hear the word “savage” and it would mean something much more painful than when it’s casually batted around on social media today.

“Savage.” “Less than.” “Dirty.”

The children’s hair might be cut, their proud, traditional braids hitting the floor. They might be issued a number—dehumanized. Or they might get a new name, different than the one lovingly selected at their birth. They might be separated from their siblings and feel alone in a strange place. They might know the ache of hunger: for their families, for familiarity, for the nourishing food their parents grew, hunted and trapped.

My reality—as an Indigenous woman from Kwakiutl First Nation (Vancouver Island), raising a kid in Abbotsford, BC in 2019—is so different. I don’t know what it means to carry a child in my belly, fully aware that in five short years I would no longer be able to protect them, tuck them in at night, or hold them whenever I pleased. I can sign my kid out of school any time I want, and sneak him off for a special ice cream treat, just because. And yet a few generations ago, Indigenous moms would be told that spending time with their children on school breaks was a privilege, not a right.

The contrast is so shocking.

I knew what awaited my son in kindergarten: Cheerful construction-paper cutouts, story time, songs and healthy snacks. I knew he would be returned to me safely. I knew he would be cared for competently. Worst-case scenario, some kid would let him in on the secret that other moms bake cookies from scratch instead of buying them at the store (shh!), or he might scrape his knee on the playground. At the end of the day I would kiss his booboos better and all would be forgotten.

I actually didn’t learn about residential schools until my tenth grade social studies class. From my 14-year-old perspective, it sounded awful, but I lacked any real context to understand what it truly meant.

But as an adult, I went into the criminal justice field, working with residential school survivors and their descendants—first as a secretary for a government department involved with residential school claims, and later in the federal prison system.

I read the survivors’ stories and I felt sad. But I wasn’t a mom yet, and there’s a difference between being intellectually aware of the objective awfulness of something “historical” and fully understanding what it means. Seeing it in print, as a hypothetical, versus the moment you look at your own child—and truly grasp the pain of those words—are emotional reactions that are miles apart. The empathy is so crushing, it almost takes your breath away.

Until I dropped my son off on that first day, I didn’t know what the trauma of residential schools really meant. That’s when it hit me—how those moms must have felt. It made me want to put down my coffee and hug him tight for just a little bit longer, but he was off and running, happy to join his peers.

I can’t do anything to change what Indigenous families went through for generations, but my heart breaks for them. All I can do is share the truth of that piece of history, with the hope that Canadians never forget. Every time we stand in the schoolyard at pickup, or our kids step off the school bus, we need to remember how lucky we are to bring our children home safe at the end of the day.

This article was originally published online in June 2019.

PARENTING TIPS

PARENTING TIPS PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY BABY CARE

BABY CARE TODDLERS

TODDLERS TEENS

TEENS HEALTH CARE

HEALTH CARE ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS

ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS