Build a Strong Foundation for Your Child’s Reading

written by Judy Kucera, M.A., M.Ed., A/AOGPE

A first grader read the word big as bag and the word saw as was.

A third grader on a spelling assessment wrote the word train as chain and the word drive as jive.

A fifth grader read the word prod as pod and the word snip as spin.

What do all of these errors have in common?

A basis in weak phonological awareness skills.

When I first started teaching that wouldn’t have been my answer. I would’ve thought it was weak phonics skills. Or, maybe they weren’t listening to the words so they had attention issues. But, as I’ve learned more and more about the skills it takes for a child to master reading, I see that the true basis of many reading and spelling issues is a phonological one.

Phonological, phonemic…phoneme…?

Let’s take a moment to define these terms.

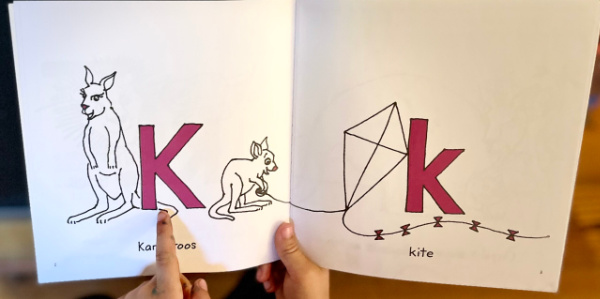

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a word.

For example, the word “cat” has three sounds in it: c…a…t. So, it has three phonemes. The word “this” has three sounds in it too. Th is one phoneme because it’s one sound made by two letters. A phoneme can be made of multiple letters. Think of the word “weight.” It has three sounds or phonemes – the first is the w sound. The second is the a sound made by eigh. The third is the t sound.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to recognize and manipulate phonemes.

For example, if I have the word cat and change the beginning sound to b, I have the word bat. If I have the word limp and I change the i sound to a u sound, I have the word lump.

Phonological awareness is a broader category. It includes phonemic awareness, but it also includes syllables and parts of words, not just the smallest phonemes.

For example, if I said the word sunflower without the sun, I would say flower. If I said the word careless without the less, I would say care. I’ve just demonstrated phonological awareness.

Phonemic or phonological awareness relates only to speech sounds, not to alphabet letters or sound-spellings. It is not necessary for students to have alphabet knowledge to develop a basic phonological awareness of language. It focuses on the auditory, not the visual. It is their awareness of sounds in the language. It can be done with your eyes shut!

Why is it so important?

The research is clear – if the auditory memory does not hold onto phonemes (a child can’t hear and remember that the word frog has four distinct sounds f, r, o, g in it…) the child has nothing to link to when seeing the letters. Their visual memory has no auditory memory to connect sounds to the letters on the page, so letters are meaningless. It is a critical skill needed to store words for retrieval both for reading and spelling.

You can’t skip phonemic awareness! A student without it will have a weak foundation in reading skills, especially as expectations become more demanding. One of my go to’s when an older student is struggling with reading and spelling is to test their phonological awareness. Inevitably, it’s weak and explains their difficulties. They don’t have an auditory foundation to build their reading skills on! But, according to one of my favorite reading researchers, David Kilpatrick: “There is no statute of limitations on training phoneme awareness skills when they are weak.” So, how can we train these skills?

How to help your child with phonemic and phonological awareness:

The best way to build phonemic awareness and auditory memory is through auditory word manipulation. The good news is that this is easy to do and requires almost no materials! And, kids love these because it’s like a game and they don’t have to read anything. I start out each reading lesson with auditory word manipulation as a way to “prime the reading brain.” Here’s some strategies for you to use at home.

Help your child build phonological awareness by:

- asking them what sound they hear at the start of a word. Ex. what sound do you hear at the start of broccoli?

- enjoying rhyming games, making up silly words that rhyme. Ie. Hannah, banna, fo fanna!

- reading rhyming books and encouraging them to listen for the rhyme.

- playing I Spy with my little Eye…something that begins with buh!

- having your child sort items by their initial sound. Fill a bag with all the small items they can find that start with a letter sound!

- segmenting words-tell your child a word and have them break it into its sounds. “Throw” them the word and have them break it onto their fingers. Ex. “I’m throwing you a stinky fish! Catch fish! f..i..sh!”

- blending words-tell your child that you’re going to say a word but stretched out, and have them guess which word you said.

- playing with words-what would butterfly say without the butter? how many sounds do you hear in the word black?

- playing vowel sound jump! Teach your child to hear the difference between long (the name) and short vowels by saying a word and having them make a long or short jump! Snack would be a short jump! Snake would be a long jump!

- counting syllables. Teach your child to hear the syllables in words and count them. Use the chin drop method vs. clapping. Hold your hand under your chin. When you say a word, your chin will drop slightly for each syllable. Ex. cat..er…pill..ar. Four chin drops equals four syllables!

Tip: **Remember that these activities are about sounds…not spelling. When you give your child any of the activities above, make sure you’re saying the letter sounds, not the names. So, I would say “What would cat say if I switched the kuh to a buh?”

Building a strong foundation in sound awareness early on will pay off in a huge way as your child moves on to more complex reading and spelling skills that require strong auditory memory. Don’t underestimate the power of phonological awareness!

And a final note on… the dreaded b vs. d confusion!

So many kids struggle with confusing b vs. d! There are many, many strategies out there to cure this. But, I wanted to share with you the cue that I use. It focuses on an auditory strategy based on the visual appearance of the letters.

First, notice that there’s a flat line at the beginning of the letter b – it’s reminding your lips to make a flat line. You have to make a flat line to make the b sound.

There’s no flat line at the start of the letter d. It’s reminding you to keep your lips open.

So, the cue when your child makes a mistake: “Oh, what is the letter telling you to do? Is there a flat line first? Then make your lips flat! / Is there not a flat line first? Then keep your lips open!“

You can even practice drawing their attention to your lips and pretending to say the b or the d sound without actually vocalizing it. Ask them, what sound am I about to say? How did you know? Yes, my lips were flat! This same strategy works for p and g!

About Judy Kucera

Judy Kucera’s teaching career spans almost 25 years and every grade level. She has taught high school English, English as a second language at a Russian boarding school, preschool special education, general special education, and now works as a reading and writing specialist in Holderness, New Hampshire. She has a bachelor of arts in English – Journalism, a master of arts in nonfiction writing, and a master of education in early childhood special education, as well as teaching certifications in pre-K to 3rd-grade special education, K to 12 special education, 5 to 12 English, and K to 12 reading and writing.

KEEP READING

Good Book Series for 1st Graders

Pros & Cons of Bob Books

Elephant and Piggie Books

PARENTING TIPS

PARENTING TIPS PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY BABY CARE

BABY CARE TODDLERS

TODDLERS TEENS

TEENS HEALTH CARE

HEALTH CARE ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS

ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS