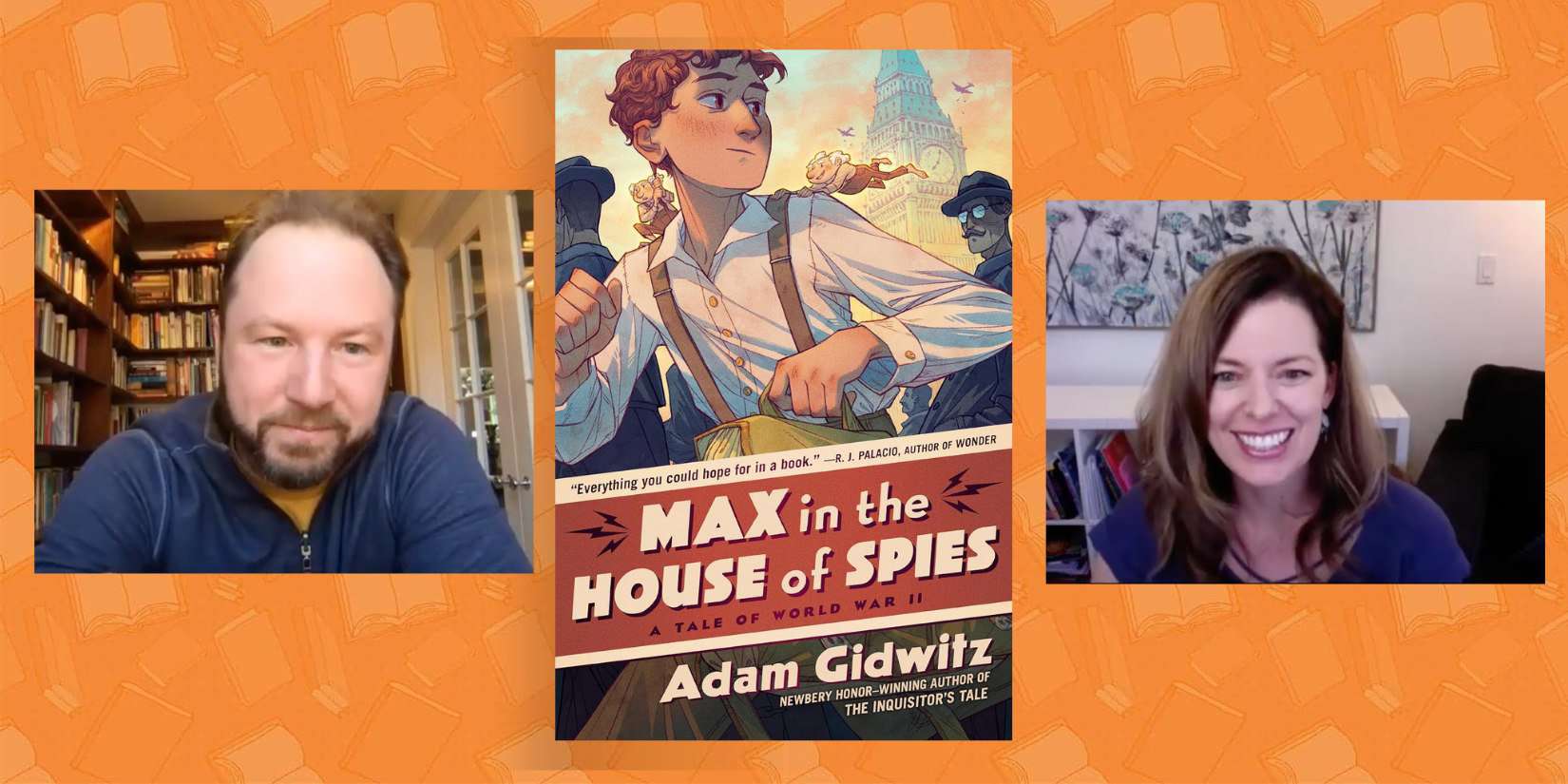

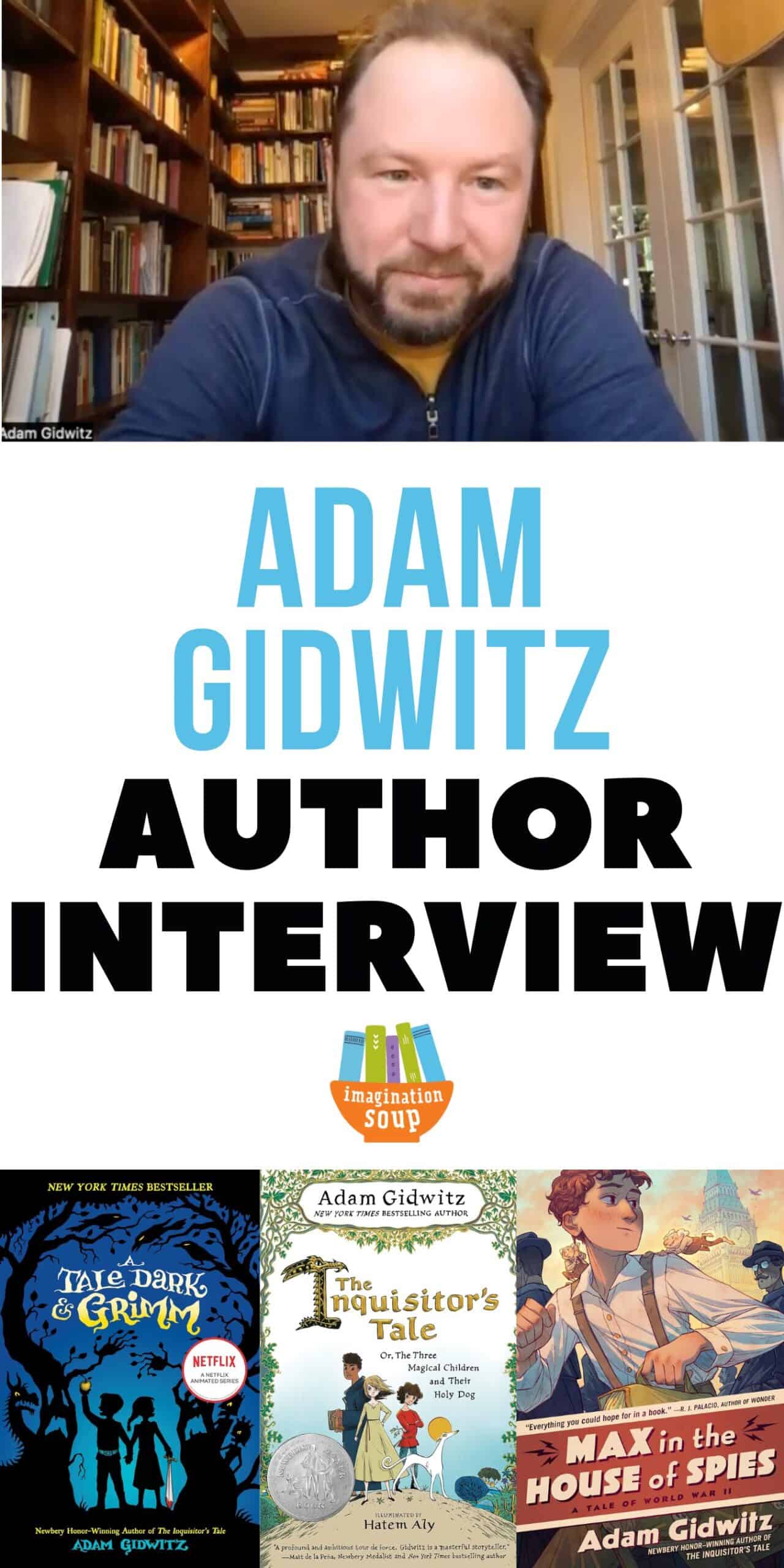

Adam Gidwitz is a prolific and unique children’s book writer of middle grade and chapter books. In our interview today, he shared his journey of storytelling and finding his unique writing voice, as well as the inspiration behind his new book, Max in the House of Spies.

Gidwitz’s books are what I like to call voicey (strong narrative voice,) and they engage readers with humor, adventure, and excitement. Not only are they fun-filled, but they are also meaningful and multilayered with big ideas. Truly, Gidwitz is not afraid to tackle hard topics and big questions. This is the genius behind his writing — the layers, hooks, and brilliant storytelling.

Max in the House of Spies is Gidwitz’s latest book. It’s set in World War II, and while it is about a dark time in history, it’s not a heavy book. It’s spy thriller filled with humor and adventure, two hilariously grumpy mythical creatures, and many difficult questions. Aka. perfection in 298 pages.

Listen in to our conversation (or read the transcript below) to hear the inspirations behind the story, Gidwitz’s journey from teacher-storyteller to writer-storyteller, and the advice Adam gives aspiring writers, children and adults!

Check out Melissa’s book talk on Max in the House of Spies

Melissa Talks with Adam about Max in the House of Spies, Writing, & Unanswerable Questions

Shop Adam Gidwitz’s Books

READ THE TRANSCRIPT.

Melissa:

Hi, Adam. Thank you for talking to me.

Adam:

Thank you so much for making the time for me.

Melissa:

Well, I’m I’m thrilled because Max and the House of Spies is my favorite book. And, all your books literally, it’s so annoying. No. You’re so talented! All your books, I’m like, this is my new favorite book. And it’s really interesting even with the Grimm books. I was like, how do you keep it’s really rare, I think.

Maybe not super rare. It’s maybe, like, 30% that authors continue to have books that are exceptional in the series, you know? So I think you do a really good job with that. And, also, you’re, like, the voiciest writer out there, I think. Don’t you?

Adam:

Thank you. I mean, my editor once told me When we were working on Inquisitor’s Tale, and in fact, I was worried about losing my voice and not sure how to write it, My editor said maybe the kindest thing that she’s ever said to me. She doesn’t tend to say kind things to me. My editors are really one of those tough editors, like tough love kind of people. But she said to me, “Adam, I would recognize your writing if it was scrawled on a cave wall.”

And I was like, okay, I think that’s a good thing.

So I guess so. And in fact, when I first started writing, I was writing because I started writing because I was telling stories to students. I was a teacher and I started writing by reading them a story out loud that I was writing for them. Every night, I would write a chapter and read it to them the next day. And then, when I wanted to try to get published, I went I quit my job and I started to revise the book. And what had been a 100-page book became a 400-page book, and as I was revising it, I was like, you know, if it’s gonna be published, it’s gotta sound like like Johnny Tremaine.

You know, something classic. Right? And so I took all the voice out of it. I tried to make it sound, you know, like objective, and the agent that I took it to read it and was like, “No, we’re not gonna publish this, and I can’t help you.”

And then I went back, and I was telling stories again to these students, and I told them fairy tale. And afterward, one of the little girls came up to me, and she was like, you should make that into a book. And I wrote it down exactly the way I told it to them with all my jokes and warnings right in it, and I sent that to the same agent, and she was like, this will make into a book. And I realized it was what I had just rediscovered was the voice I used to speak to children. You know, I had kind of rubbed out my voice when I was revising it.

And so if my book sounds voicey, it’s literally just because that’s how I talk to kids.

Melissa:

Yeah. And you’re an oral storyteller.

So I used to be a teacher too, and I always thought there were kids who are summarizers and kids who are retellers. Right?

Adam:

Oh, that’s interesting.

Melissa:

Like, what’s a movie about?–and the kid who takes 20 minutes, and they don’t really even get to the point. So maybe, let’s teach you (reteller) how to summarize. But then there’s the kid who’s just, like, it’s about a boy and a dog, and that quick summary. So you’re this oral storyteller who knows how to craft a good story.

Adam:

Retell the story. I don’t know if I know how to summarize. You know I also get lost in the details, but I’m like, it’s a good story. You gotta hear everything.

Melissa:

But that makes it a good writing transition because then you have that. I’m working on being a better storyteller.

Adam:

I doubt that. I have read the articles, and they’re excellent. But honestly, it is very different, like, writing an article. I feel like I’m bad at it. When when, you know, I publish it or something, and I was like, could you write an op ed about this? I try, and I just get lost.

Melissa:

Mhmm.

Adam:

Because first of all, when I’m ready for kids, I feel like I understand kids much better than I understand adults, honestly. Like, when I’m talking to adults, usually, I’m like, I don’t know what you’re thinking. But when I’m talking to a kid, I know what they’re thinking. But the other thing is, You know, when you’re writing an article, you have, like, you’re making a point, and I don’t make a point when I talk. I try to make lots of points. In fact, I try to ask lots of questions and sometimes a point comes out of it, and sometimes it doesn’t. So if I were to write an op-ed, I would wanna write something, like, suggestive that asks a lot of questions, and nobody must have understood.

Melissa:

Yeah. It’s okay. We could partner. I’ll help!

Well, that’s a good transition into the timing of this book that couldn’t be more perfect. And also, I mean, you just get chills about the timing. So, what do you want the world to get out of this book? And how would you suggest people use it with children? In the classroom, and the library, and home –I mean, that’s a really big question, I know.

Adam:

I’d love to answer it, though. Yeah. So, I mean, first and foremost, what I want people, kids and adults to get out of the book is to have a really good time reading it. It is a spy novel. It is an adventure. It’s supposed to be funny. I hope it’s funny. I have this very deep-held philosophy that as a writer, your very first responsibility is to get your readers to turn the pages. If they’re not turning the pages, then it doesn’t matter what big highfalutin idea you have in the book. They’ll never get there because they’re not reading the book. So mostly I want people to have fun. That’s first.

And then if they’re having fun, the idea in the book, I think there’s hopefully a lot of ideas in the book, but the one that animated both Max in the House of Spies and the completion of the story, the second in the duology, Max in the Land of Lies, which will come out next year.

Melissa:

Okay. I did wanna ask, next year? Because I can’t wait. Can I get a preview?

Adam:

Yeah. I’m sure we can get one.

Melissa:

That ending! I’m ready. I can’t wait.

Adam:

Oh, good. I’m glad. Yes. We can definitely get you a book.. Okay. And it is finished. And the major question in it is, between what is right and what you love, how do you choose?

When I speak to kids at schools about this book, which I’ve started doing, I ask them this big question. I actually use the Albert Camus quote that’s the inspiration of the book, and it was only part of it. I say, “Between justice and my mother, I choose…” and then the kids debate it.

And then we have this really interesting conversation at every school I’m at where these kids, you know, a lot of a lot of times it goes mom first. You know, she made me, and then they’ll swerve over to, well, but my mom is just one person, and justice is for everyone. You know? And then they try to sort of bridge the gap. My mom would want me to choose justice, or there’s no justice without my mother in the world. You know, all sorts of things. I had one little boy say, he was quite young, probably too young for the conversation, and he said, my mom because she cooks.

And I was like, yes. And he goes, cookies. And I was like, yes, she makes cookies. But sometimes they ask me, Well, what’s my answer to the question? And my answer is I don’t have an answer. If I had an answer, I wouldn’t have asked it.

Melissa:

Mhmm.

Adam:

My editor, who is a wise person in addition to not being very nice, said that my best books are the ones that have questions in them that I don’t know the answers to. And so when the kids and adults are reading this book, what I’m hoping is that they will wrestle with this question of, you know, I might feel an emotional affinity to this answer, and I might feel that this answer is just or right.

Melissa:

Mhmm.

Adam:

And how do I choose between them or navigate that gray space between it? And you said, you know, this is quite a moment for this book to be coming out. And it feels like all around the world, whether it’s politics in this country, it’s war in the Middle East, it’s a host of issues. We may have one emotional affinity and then one sort of rational or moral affinity. And how we navigate the overlap between them or the lack of overlap between them kind of determines what our moral presence is in the world, and it’s not easy. I don’t pretend I know how to do it. What I’m asking young people to do is to wrestle with that while also hopefully, having a great time reading.

Melissa:

Yeah. You mentioned it might have been the author’s note about the fake news. Were you really wanting to start writing this book because that? Well, I mean, for a variety of reasons, but that was one thing. And even the Allies had the propaganda just like the Nazis did. How do you help kids navigate that in our world today? I mean, is that another, like, humongous question?

Adam:

It’s really complicated.

Melissa:

Right? Yeah.

Adam:

I mean, there are people in history who have obviously been bad. The Nazis obviously bad. And then there have been, you know, people that are complicated. Right? You know, in the book, the first book takes place in England, and they are sort of in the waning days of the British Empire.

And the British Empire has got a pretty spotty record. Right? They’ve been very powerful. They accomplished some huge things, obviously, and they also oppressed and killed a lot of people along the way. You know, when I talk to my South Asian friends about Winston Churchill, they think of him as a butcher. Right? They made 3,000,000 people in India starve right during this period when he was being a hero in World War 2.

So we have a lot of affinities, a lot of loyalties. And sometimes there is something that is, like, obviously good, you know, our families. But even our families, you know, sometimes our parents do things that are not really good. And so, how do we navigate those loyalties, and how do we maybe reexamine them or at least problematize them? Like I will always be loyal to my family, and I can also see some of the errors that they make and some of the things that I wanna distance myself that I disagree with.

Melissa:

Mhmm.

Adam:

Did that answer your question?

Melissa:

I mean, yeah.

Of course, I wish you had said, like, you know how to get kids to think critically, and then you just do, like, these three steps, and you’ll be good. Yeah.

Adam:

Honestly, the way I think you get kids to think critically is you tell them a good story they care about, and then you ask them a question you don’t know the answer to. That’s what we choose to do.

Melissa:

Yeah. And if we could do that for adults right now, boy, that’d be something.

Adam:

Yeah. Honestly, I think it’s easier to get kids to think critically than adults.

Melissa:

I agree. I was a literacy trainer for a while, and I was like, I think I like the kids better. The adults are a different whole situation.

Adam:

I’m with you. I absolutely choose kids every time.

Melissa:

Yeah. Exactly. And the kids still think I’m funny.

Adam:

I think you’re funny, but, yes, I agree with you. That’s how I’m in the world, too.

Melissa:

Yeah. Tell me how you chose or what you were thinking behind the dybbuk and the kobold?

They were so hilarious. I just loved them so much. And I’m also seen a lot of your interviews as I was doing prep and I know you all are a big mythical creatures fan. Me, too.

Adam:

Well, thank you. I’m so glad you liked them. They, you know, the first impulse behind them was that if this is gonna be a book about a kid navigating World War 2 and Nazi Germany. It’s gonna be, like, dark, and it could get heavy, and I don’t wanna write a heavy. I wanna write books with heavy issues, weighty questions. I don’t want it to feel heavy again, because I want kids to turn the pages, and I want kids to enjoy turning the pages. And so was important to find a sense of humor, and so they were very clearly the debate of the creatures Stein and Berg, who are on the left and right shoulders, are an opportunity for humor, but I also wanted the kid in the book, just like the kid in real life, not to feel alone.

In a lot of my books, there is a storyteller’s voice that cares for the kid, that says, oh, this part’s gonna be scary, and that, as I said, literally comes out of my experience telling fairy tales to kids in classrooms. Right? I take care of the kids.

And so when I write the book, somebody needs to be taking care of the kids. And so often in my books, it has been a narrator.

Melissa:

Mhmm.

Adam:

And in this book, I tried two immortal creatures that appear on Max’s shoulders. They are taking care of both kid readers, but also they’re kind of despite being there to heckle and annoy Max, Ultimately, their presence is taking care of him too and giving him sort of a non-kid, a kind of adult voice to at least chat with. Mhmm.

Melissa:

Well, and they had their own arc also, which was kind of fun.

Adam:

I’m glad that that came out, and their arc gets even more pronounced in the second volume.

Melissa:

I can’t wait. That’s and so book 2…when does it come out?

Adam:

Yeah. I mean, we don’t have a pub date yet, but I am praying it’ll be, February of 2025, so soon soon in the New Year.

Melissa:

Great. You never really know with these things. Right?

Adam:

Yes. But we’re far along in the editorial process. Feel pretty good about where we are.

Melissa:

Okay. Good. Yay. Do you find inspiration everywhere? Where do you get your ideas?

Adam:

My ideas, first of all, come from, not to sound like a broken record, but, like, from problems that I don’t know the answers to, the things that are bothering me. So you talked about fake news a little bit. You know, it was the early days of the pandemic, and it felt like everyone was lying. And it wasn’t clear whether people knew that they were lying or not. Right?

Melissa:

Yeah.

Adam:

Some people you were pretty sure they knew. Other people you were like, I think they think they’re telling the truth, but it turns out what they said last week isn’t Is it right? You know, am I supposed to wear a mask or not? I mean, I heard very earnest people on both sides of the debate about masks. I didn’t know the answer.

Melissa:

Yeah.

Adam:

So, as I was, you know, feeling that problem of, like, there are people out there who are lying, and they may not know it, And those people who do know it, why? Why is it okay with them? And why are the people who are believing lies, believing things that they are too smart to believe. Right? You know, I don’t wanna, make anyone out there feel stupid, but the people who injected bleach into their veins and died. Right? That happened.

Melissa:

Oh, I didn’t know that.

Adam:

Yeah. Yeah. Somebody injected bleach into their veins because You said that’s how you could cure COVID. Right? We know you don’t inject bleach into your veins. Right? So what happens when you short circuit your own thought processes to believe somebody? Why do you do that? And that question made me think about the Nazi period, where Germany had been the most educated country in the world. Its, you know, its epithet was, the the land of poets and thinkers is what it was called. And then this guy arose, Adolf Hitler, who was like, I will make this country strong and powerful again, but you just have to believe all of the hateful things I believe: The Jews are bad, the non-white people are bad, the gay people are bad, the disabled people are bad. You have to believe all that stuff, and Germany said yes. They decided to believe it.

Melissa:

Intelligent, educated people.

Adam:

Right.

Melissa:

I’m seeing some of that today.

Adam:

Yeah. And so that’s what was driving me crazy, and that’s what I wanted to explore. So the idea comes first from this question, and then I start reading. And I read stories about, Nazis. I mean, not just stories. I read history, like, historical stories about Nazis, and then I start reading about spies, and I read about radio and the way propaganda is used and spying with radio, and all of those things, like, I just they’re exciting things in each of that would make a good story. That would make a good story. And I just make them another list, and then I’m like, okay. Now, I start to see my story coming together.

Melissa:

Oh, okay. When did Max come in? Did you have all that research, and then he popped into the story?

Adam:

Well, in some ways, Max was kind of there before even I was asking those questions because a close family friend of mine, I wrote about this, I think, in the afterward of the book, was a man named Michael Steinberg. Michael was a music critic back in the seventies, eighties, nineties. And he was a close friend of the family, and he had been on the Kindertransport. He had been one of the children taken out of Nazi Germany, sent out by his mother to a country, England, that he didn’t know anybody in, didn’t speak the language. And when I explain this to kids, and not everybody knows this, the reason they had to send their children is because England agreed to take 10,000 Jewish children, but not their parents because they had too many Jews already. So, Michael went, and he was one of the lucky ones. His mother survived the war and was able to join him afterwards. Most of those kids, their parents did not survive the Holocaust.

Melissa:

Yeah.

Adam:

So that story was always in my head as an amazing story that I felt like would be ripe for telling as a book, But I didn’t know, like, what else I wanted to say about that. And so when this question about lies came up, That seemed to dovetail together really well, and I had been reading a lot of wonderful books, by John le Carre spy novels. He’s, I think, one of the greatest novelists of the last 100 years. And, also Ben MacIntyre, who writes some of the most the best nonfiction books that I’ve ever read, which are spy, nonfiction books. And so between, like, my new excitement about the spy books and this question I was wrestling with and, Max / Michael story that always been in my brain, those are the 3 ingredients that came together to make the book.

Melissa:

Yeah. I love how it’s it’s not a straight historical fiction novel because it’s this mash-up, which makes it so compelling to read, I think. You know? I wouldn’t even say fantasy I don’t know how magical ish, fantasy ish?

Adam:

Yeah. I mean, I think of it as historical fantasy.

Melissa:

Okay.

Adam:

Yeah. But, I mean, it is more fiction than fantasy, for I mean, more historical than fantasy, for sure.

Melissa:

Right. But it’s everything works, which is and I don’t see that as much as I would like to. There are certain authors where you’re like, you did it.

Adam:

Yeah, it’s a fun way of doing it. I mean, I think I first kind of, got the idea for historical fantasy in Inquisitor’s Tale because it’s this world where I knew a lot of the history. My wife was a professor of medieval history, and so I was encountering the history a lot. But also they had all this folklore that, felt, like, so rich, and why not take their belief system seriously? Why not say, well, I know none of that really happened but they believed it was happening. They believed they were dragons. Yeah. We found dinosaur bones. Right? It’s comprehensible why you would think there were dragons.

Why not take their belief system seriously and and combine the history that we’re pretty sure did happen with the mythology that they were pretty sure was happening?

Melissa:

Mhmm. And it worked. That was really innovative, too. Thank you. Okay. Is there anything else you wanna say about the book? I just wanna be respectful of your time and anything you wanna say for writers who are who are gonna listen and read this interview.

Adam:

Yeah. I mean, I have a million things that I could say to writers. I say different things, you know, things to kid writers and other things to adult writers. To kid writers, I always say that the most important thing that you can do is spend as much time as you can imagining. Everyone says read a lot, and, yes, reading is super important.

And if you wanna be a writer, you should write. Yeah. That makes sense. Definitely. Mhmm. But even before you write, if a kid, you know, spends time imagining, be it reading, be it playing, you know, with toys or talking to themselves in their room or out on the basketball court telling themselves stories as they’re shooting hoops. I know I used to do this all the time pretending I was an NBA star. Like, all of that is writing, and, you know, eventually, you’ll write it down.

So that’s what I tell kids and for the grown ups out there who are writing. For me, it’s it’s that I have to think really honestly about my readers, really honestly about whether they’re gonna be enjoying it. So not only do after I write my books, I read them out loud to myself and not under my breath, like, out loud out loud.

Melissa:

Yeah.

Adam:

And it means you gotta find a quiet space. I do it in the park. People in my neighborhood think that I’m, the local, you know, crazy person, but that’s what I do. And I and I have to read it out loud because, We have been hearing language a lot longer than we’ve been reading, and so our ears, Our actual ears are very attuned to what language sounds like. And it’s exhausting to read it out loud, not just because you’re producing your voice, but because It’s this radical act of empathy where you are imagining the people who would be listening to it, and are they, like, ugh, that’s lame, or, ugh, I’m bored. Mhmm. Because you have to be really honest and hard on yourself.

Like, is this really funny? Is it really exciting? Now, that doesn’t mean I recommend, like, tinkering forever. Tinkering forever is not good, either. Yeah. Once it feels good, yeah, you could change this, you could change that. But if you’re like, man, I love this. It’s funny. I can’t stop reading it myself. Then it’s time to share it with the world, and then don’t be shy. You gotta you gotta be gotta be courageous to put your writing out there.

It’s not easy.

Melissa:

Good advice. I worry with the kid writers with all that it’s just, I think about this for myself, too because am I stuffing my brain full of something every single moment? Even if it’s even if it’s good books. Not even TV or shows, but it’s so much input. So sitting quietly and imagining, it’s sort of this lost skill in a way.

Adam:

Unfortunately, that is true. Yes. Getting the kids away from the electronics, you know, if you’re a parent or a teacher or whatever is so crucial. And that’s why I write in the park, actually, because I don’t get Wi-Fi out there. You know? Because the Internet is now more powerful than I am. I you know, it’s like I’m likeI just need to research one thing. You know? Like, I just need to look up, you know, whatever, how long it took to fly a bomber from Berlin to London or vice versa. Mhmm. And then, you know, an hour later, I’m like, what happened to my writing time? So, yeah.

Get away from the Wi-Fi signal if you can. The Internet will not help you write a book, but your imagination will be the muscles that you use to write.

Melissa:

Yes. Yeah. Okay. Anything else you wanna say before we wrap up?

Adam:

No. I’m so grateful that you read it and enjoyed it. I’m really humbled by that. Thank you.

Melissa:

Oh, yeah. I really loved it. And I, I can only aspire to be as voicey as you one day. I just love it.

Adam:

You have a great voice, and it’s gonna be your voice. It can’t be my voice.

Melissa:

Yeah. I have my own voice. It’s that you sometimes compare yourself with other writers and, you know, it’s different. I remember when I first started freelancing, I was like, do I call myself a writer? And I was like, well, yeah. I write. It might not be very good, but I’m a writer. I make money.

Adam:

That’s that’s an exceedingly rare thing. Being a professional who makes money? That’s a hard thing to achieve, indeed.

Melissa:

Yeah. I left the classroom thinking, what will I do next? Oh, writing! Because that is so lucrative. I don’t know what I was thinking, but it’s it’s okay. It worked out.

Adam:

It’s working out.

Melissa:

Yeah. Well, thank you so much for your time.

Adam:

It’s such a pleasure talking to you. Yeah. Thanks so much.

Melissa:

Thanks, Adam.

KEEP READING

PARENTING TIPS

PARENTING TIPS PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY BABY CARE

BABY CARE TODDLERS

TODDLERS TEENS

TEENS HEALTH CARE

HEALTH CARE ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS

ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS