As a white settler parent, I believe that it’s my responsibility to talk to my daughter about race and colonialism, and I try to take every opportunity I get. She has marched with me at rallies in support of Indigenous land rights, especially the Wet’suwet’en in BC and the people of Grassy Narrows First Nation in northern Ontario. We’ve walked together with thousands of people to honour the children who died in residential schools and read powerful books about the subject, like Shi-shi-et-ko by Nicola Campbell and Stolen Words by Melanie Florence.

But these conversations and actions are not always easy. I sometimes find myself stumbling through them, questioning myself and wondering if I’m doing enough, saying enough or telling my kid too much. But more and more as my daughter gets older—she is six now—I find that she is interested and asking questions. She is often ready to spot racism and injustice, she is beginning to know what colonialism means, and she asks about those unkind schools that children were forced to go to.

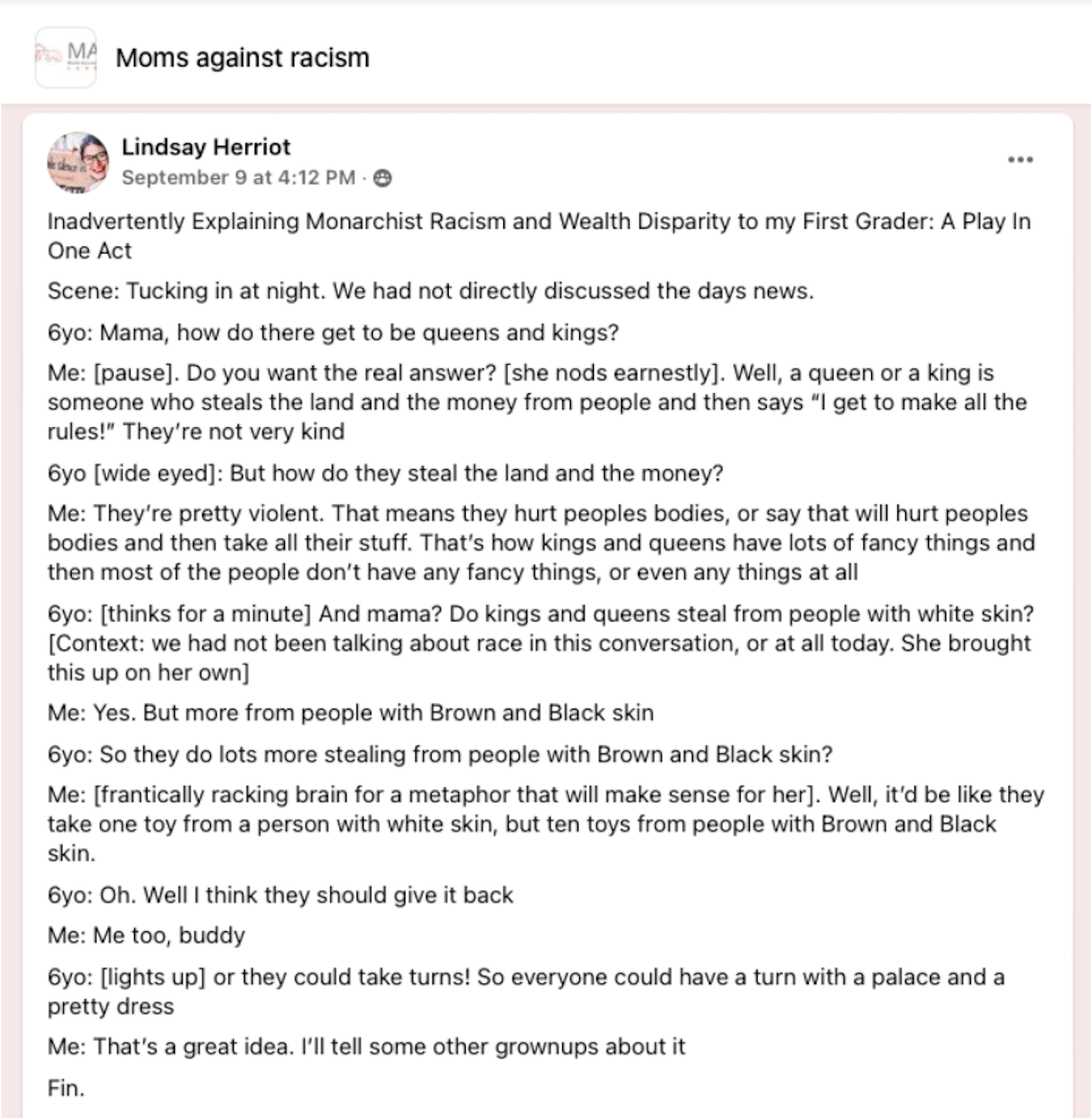

As I was feeling uncertain about whether I should talk to my daughter about the Queen’s death—after all, she still barely knows that the Queen existed at all—I came across a social media post by Lindsay Herriot, a mother of three young children and a member of the facebook group Moms Against Racism.

Photo: Moms Against Racism on Facebook

Herriot, a white parent, often posts glimpses of her family’s anti-racist conversations on the group, like this one she had with her six-year-old after the death of the Queen. Reading her conversation with her daughter helped push me to have the conversation with my daughter, too. And this is so often the case; reading and listening to others from all backgrounds who are working to dismantle colonialism helps push us to do better, as a parent and as a person.

“I write and share these vignettes as one-act plays to encourage other parents, and especially other white parents, to take up these conversations with their own kids,” says Herriot. “And I try to include in them the humility that how our family is approaching this is by no means the best or ideal way for these conversations to go. Rather, they’re an imperfect snippet of how one family is trying. And hopefully, it will spark the confidence and creativity in other parents.”

There is a growing awareness of how important it is to challenge colonialism and racism in all its forms. Being a part of groups like Moms Against Racism and Standing Up for Racial Justice is one way parents can learn and challenge themselves. I chatted with Kerry Cavers, the Black mother of three who founded Moms Against Racism two-and-a-half years ago after the murder of George Floyd. It is now a volunteer-led advocacy organization as well as a parent community (while they currently connect on Facebook, there are plans to move to a new forum soon), and offer training in “How to Raise an Anti-Racist Child.”

What inspired Cavers is that these are conversations parents in the group will be having from the time children are very young, until they are teens, young adults and beyond. “I see Moms Against Racism as an opportunity for a generation of anti-racist kids to be raised,” she says. “We know that as parents, as people in mothering roles guiding children, we have a very unique opportunity to influence the future.” Cavers shared her best tips for talking to kids about racism and colonialism.

Every parent should be having these conversations

“I think that parents, all parents, no matter what race, have a responsibility to be talking about racism and colonization,” says Cavers. “Racism is not just a racialized person’s problem. It’s a white person’s problem too—it just impacts each of us differently. And we have different responsibilities and accountabilities within dismantling systemic racism.”

Listen to those with lived experience

For families who haven’t been on the receiving end of racism or colonization, Cavers says to look towards those people who do and try to see what they’re seeing. “Look at Facebook pages like Moms Against Racism or Parenting Decolonized or Untigering, more so the BIPOC people in those spaces that are giving that parenting advice,” she says. “They’ll give you those perspectives, that insight, that not having that lived experience, you may miss.” Prioritize the voices of Indigenous peoples to learn about settler colonialism in Canada, and listen to people who have been displaced, disrupted and had to fight for independence in countries of the global South.

Ensure this kind of thinking becomes second nature

While many parents may feel daunted by the idea of talking about big topics like the Queen’s death, racism or colonization, Cavers says the way to make it easier is to be having these chats all the time. “That way, it becomes just a matter of your family’s values,” she explains. “You may not have all the answers or know all the information, but if you’re having bite-size conversations here and there, you’re learning and growing alongside your children, and learning where they’re at, and how ready they are to receive certain information.”

Herriot, who shared the one-act play with her daughter, says she’s been having these conversations since her oldest child was an infant. “Even as a tiny newborn, we were talking to her and explaining to her what’s going on in the world and how we as white people need to show up and get loud about anti-racism. Because anti-racism conversations have always been part of the fabric of our family, they’ve evolved naturally. There’s never been one Big Moment where we’ve needed to introduce race or white supremacy because it’s always just been there.”

While I was a bit in awe of the conversation Herriot had with her first grader, it’s the direct result of Herriot’s long-term commitment to educating her child about racism: “In the vignette I posted about the Queen, my six-year-old brought up a racial critique of monarchy all on her own,” she says. “I think that’s because she’s used to a racial justice dimension being integrated into our conversations about all sorts of topics.”

Follow your kid’s lead

For parents just starting out, Cavers recommends asking open-ended questions. “Ask them things like, ‘So what do you think about …?’ or ‘What have you heard about …?’ And let them tell you what they know,” she says.

You can then follow up by asking if they have any questions. “Then they’re asking you the information that they need to know, at an age-appropriate level, because that’s where they’re at,” she says. “As parents, we have so much more understanding and context that I think we scare ourselves that we need to tell our kids everything all at once.” If we let our kids lead, she explains, we can then let go of the fear of oversharing and start to understand what our individual children can and can’t handle.

It’s OK if you are still learning, too

It’s perfectly acceptable to enter these big conversations with kids without being a subject-matter expert yourself. “Telling our kids that we don’t have all of the answers, we’re learning this too, is totally OK,” says Cavers. “It allows for that openness for learning to happen both ways, because now a lot of kids are learning some of this stuff in school and they may bring something home that you don’t know, and it’s an opportunity to have that conversation and that learning together.” It’s good for them to understand that no one has all the answers.

Herriot agrees: “Talking about race all the time removes a lot of pressure to get it right or perfect in any one conversation. We can move through these topics bravely because it’s lots of little conversations over time. We don’t have to panic that it wasn’t perfect—we just have to keep having the conversation, over and over, all the time.”

Build on universal concepts

For many Black, Brown and Indigenous people, conversations about racism and colonization have always been an unavoidable part of life, but for many white families, this may seem like something new. Yet the chats will build on fundamental concepts that you’ve already been dealing with–just with a different, more focused lens.

“They’re building-block concepts—friendship, and empathy, and generosity, and accountability, and consent,” says Cavers. “Those are all concepts that are universal, they apply to equipping our children to be able to identify injustices that are happening, and to be able to uphold their values.” She suggests building on experiences that are familiar to your children, around sharing toys, playing together, the feelings that come with being included or excluded.

It’s less about your child’s age and more about their experience

Cavers offers a reminder that so much is going to be unique to each individual child. “Some children, through either lived experience or just their own personal characteristics, are going to be more mature and are going to appreciate being spoken to with a higher level of nuance. And then some kids need to really have analogies and have that related to their own personal experience to be able to understand it,” she says.

Her own children are nine, seven, and five. “Because we’re having these conversations all the time, even my five-year-old can handle a higher level of nuance, and they can connect those dots,” she says. “If I was just starting having these conversations, I would probably temper down my language and kind of feel things out.”

Find a diverse community of like-minded parents

For Cavers, the power of Moms Against Racism is that it allows for parents of all backgrounds to learn from each other. “I think what I’m most proud of is the culture that we’ve created within the MAR community,” she says. “We are actively demonstrating what it could look like to be part of an inclusive group opposing white supremacy, where we are having difficult conversations. We can do so without attacking or belittling each other. We can show up with humility and say ‘I was wrong, I made a mistake,’ and not be ridiculed for not knowing. There’s accountability but no attacking. We really focus on that relationship being the way forward.”

PARENTING TIPS

PARENTING TIPS PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY BABY CARE

BABY CARE TODDLERS

TODDLERS TEENS

TEENS HEALTH CARE

HEALTH CARE ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS

ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS