[ad_1]

There are many factors to consider when making decisions regarding children’s health. In the ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), vaccines against the causative agent, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), have been the target of much suspicion and hesitancy. A new preprint research paper examines the various contributions to parental attitudes regarding COVID-19 vaccination of their children in the UK.

Study: Parents’ intention to vaccinate their child for COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey (CoVAccS – wave 3). Image Credit: Tatevosian Yana / Shutterstock

Study: Parents’ intention to vaccinate their child for COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey (CoVAccS – wave 3). Image Credit: Tatevosian Yana / Shutterstock

Introduction

In prior research, it has been demonstrated that the perception of the risk of becoming sick and the perceived safety of vaccines drive parents’ attitudes toward childhood vaccinations. This is compounded by the pressure imposed by social norms, i.e., the perception that most other children have taken the vaccine in question.

Several papers have come out analyzing COVID-19 vaccination intentions on the part of parents concerning their children. Two extensive UK studies suffer from the fact that they were completed before COVID-19 vaccines for children were available. However, their findings show that perceptions of a high risk of becoming infected, acceptance of vaccination benefits in general, and trust in the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in particular, drove parental acceptance of these vaccines for their children.

Conversely, the novelty of the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and adenovirus vector vaccines decreased their appeal for parents concerned with the child’s long-term safety. Factors that increased the odds of pediatric vaccine acceptance among parents included parental COVID-19 vaccination.

In spite of initial hesitation, the vaccine gradually moved from being recommended for high-risk children to being made available to all children above 12 years old, and offered to everyone over 5 years old.

In the current preprint posted to the medRxiv* server, the researchers looked at UK parental intention to vaccinate their children during a time of selective pediatric vaccination. The vaccine was being offered to all 16- and 17-year-olds by the time data collection for this study ended, while 12- to 15-year-olds could also get it. Almost 1.5 million doses had been administered to those below 18 by then.

About a tenth of under-18s had received one or more doses, though, in the current sample, it was about 17%.

What Did the Study Show?

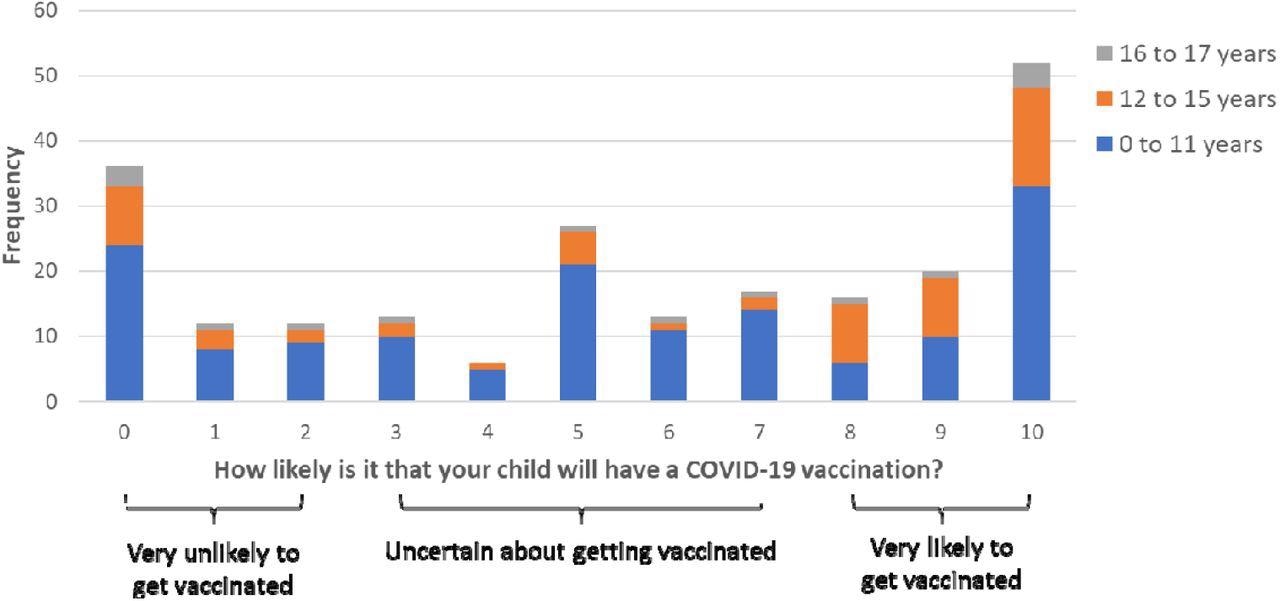

Vaccine uptake among children was low in this study, at about 17% for one dose or more. Among those who had not yet vaccinated their children, about 40% claimed to be willing to, while just over a third were uncertain. In 27% of cases, the parents indicated their unwillingness.

Perceived likelihood of a child having a vaccination (0=“extremely unlikely” to 10=“extremely likely”) by child age, with cut-off points used to categorize participants’ vaccination intention.

Interestingly, the percentage of willing parents dropped to less than half, compared to the ~50-65% of some prior studies. This could be because much of the controversy and vaccine hesitancy arose after the emergency use authorization of the nucleic acid vaccines, a novel platform that was used for the first time during the pandemic.

Over 70% of the unwillingness was traceable to parental beliefs and attitudes in three areas. These comprised the level of threat perception regarding COVID-19; the degree to which the vaccine was felt to be necessary for or widely used among children; and fears about vaccine safety or misgivings about the novel vaccine platform.

Approximately 30% of the difference in parental intentions regarding child vaccination could be attributed to social and demographic characteristics of the parents, with these factors playing an important role. Children of Chinese and Indian origin, those in better-off living areas, and those with English as their first language were more likely to get the vaccine, as were those who did not get free school meals. The chances were also higher among those with special needs.

Another 30% was explained by parental beliefs and attitudes regarding the vaccine. Those who felt that vaccination was necessary, and those who felt that the majority of children would get the vaccine, had greater willingness rates. This was also the case with those who felt that COVID-19 was dangerous to their child, and those who thought the vaccine was safe.

This agrees with earlier results, showing the importance of parental attitudes to routine childhood vaccines, and supporting what is known about the adoption of health behaviors. Moreover, it is possible that the high incidence of infection among children of primary and secondary school age, as occurred from September to November 2021 and January 2022, could make parents more willing to vaccinate their children and prevent the disease.

The single biggest reason parents chose to vaccinate their children was to protect both the child and others from infection. Some also said the child had chosen to be vaccinated. This was found among parents of older children as well, those aged 12 to 18 years, who also cited the vaccination of the rest of the family.

Parents continued to express reluctance over giving the vaccine to their children, but those who had received it intended to give it to their children, and for much the same reasons. This echoes the findings in other pandemics.

Conversely, those who were unwilling to vaccinate their children had safety concerns about the experimental vaccine platform and adverse effects, as well as not thinking that COVID-19 was a serious harm to children in general. Again, other data available with the Office for National Statistics show that fully one-quarter of parents whose children were aged 5-11 years did not intend to vaccinate the child, mainly because they were worried about the adverse effects and wanted more evidence of efficacy.

What Are the Implications?

The UK government has begun to think about a “living with COVID-19” paradigm, as opposed to a zero-COVID-19 approach. This involves vaccinating adults to prevent serious infection, while allowing social mixing, reducing testing requirements, and removing other non-pharmaceutical interventions such as mask-wearing in public.

It has been challenging to demonstrate similar benefits for vaccinated children, in part because of the low incidence of symptomatic disease and serious illness, which has contributed largely to the debate on pediatric vaccination. At this time, the vaccine is being offered and is recommended for all individuals aged 5 years and above.

While many factors interact to affect the parental choice as to vaccination of their children against COVID-19, time may encourage many parents to go ahead with vaccination as more and more children get the vaccine and the vaccine technology becomes less alarmingly new. However, simultaneous shifts may happen with the virus and with patterns of infection, as new variants arise and restrictions intended to control viral transmission are relaxed.

Conclusion

This prospective cohort study was representative of UK residents on a broad scale, but participants included only those with children aged 17 years or less, and those who completed both the first and the follow-up surveys. This might limit the generalizability of the study. However, the findings clearly indicate the mixed response among UK parents to the idea of giving the COVID-19 vaccine to their children during a period when the vaccine was available as opposed to being a possibility.

Intention to vaccinate was related to having taken the vaccine oneself, seeing it as necessary and commonplace, as well as seeing COVID-19 as a greater risk. Such parents also saw the vaccine as safe for their children.

Those who said they would not vaccinate were mostly concerned about adverse side effects, while those who were planning to vaccinate mostly said they were concerned about preventing the virus from spreading to others.

*Important notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link

PARENTING TIPS

PARENTING TIPS PREGNANCY

PREGNANCY BABY CARE

BABY CARE TODDLERS

TODDLERS TEENS

TEENS HEALTH CARE

HEALTH CARE ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS

ACTIVITIES & CRAFTS